Feeling

Straight off the first lift in Serre Chevalier (and a week riding a 19.5in Trek Slash), the HB160 took some time adjusting to the sizing, but not to the general feel and front to rear balance. The suspension felt marginally firm, but there’s decent grip, support and pedal efficiency, and the chassis covered ground quickly. The back wheel tracks well over bike park chop and holes when pulling the brakes too. After a few runs, and a couple of clicks less low and high speed compression the back tyre bit more into flat turns and the X2 felt more lively, but still with plenty feedback.

Whatever blend Hope’s British Cycling boffins are laying, the solid frame’s got a well damped feel and a dull thwack through holes and rocks, without being too rigid, brittle or twangy. The headtube area is noticeably stiff, even compared to other carbon enduro bikes. Measured static, the 340mm BB is normal, but the HB160 rides tighter in the mid stroke, so doesn’t sit in and put feet as low as some other 160mm bikes. It’s a fraction upright in man-made berms and jumps, but still has a real carve to it and good corner exit speed.

Built durable like Hope wanted, it’s over 14kg with proper tyres and the chunkiness is noticeable on flatter ground. Using Hope’s 35mm rims (2kg+ a pair) doesn’t help in the liveliness stakes, but the wheel set up has good support for wider tyres, to counter the fact they roll slowly and don’t accelerate that fast. You’re obviously locked in to a special Hope hub set up, but not necessarily the rims if you wanted to chuck even more money at wheel build choices afterwards.

After one day on lifts, the HB160 left a solid impression, but the front tyre went missing on blown out dust a couple of times, and I still hadn’t totally synced with the bars and front wheel being closer than normal. It felt like it needed stretching out a bit to shift about in, and also lowering for the bike park, especially as the frame height was affecting knee clearance with saddle slammed. This standover aspect seems a bit weird on a brand new bike now that 170mm droppers exist as well.

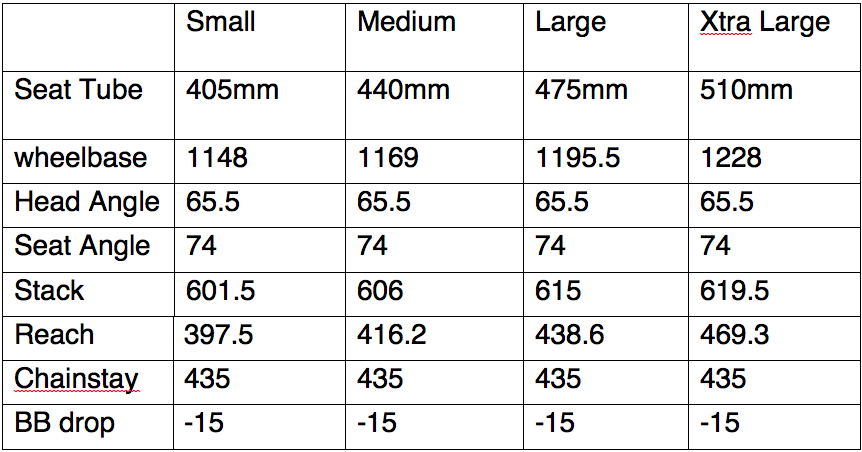

N.B. Hope has lowered the seat tube due to feedback received. S frame : no change, M frame : 5mm off, L frame : 10mm off, XL frame : 10mm off. Geometry chart above includes updates.

Our second ride was a totally different kettle of fish – a van uplift to a backcountry descent to Briançon that took in one of the steepest tracks I’ve ever half-ridden, half-scrambled. This was designer Guillaume’s typical local riding; technical footpaths and balcony trails that have eyeballs on stalks trying to process all the information to keep safe. In this raw, natural terrain, and the HB160 made good sense. Easy to pick up and turn, tighter here meant more flow in multiple switchbacks and an ability to scythe through twisty tree-lined paths. After a morning rattling rocks and hairpins, Hope’s bike had just kind of slipped into the countryside, meshed into me and got on with it. The narrower rear end really was a thing too; it does slink through tighter gaps and pointy edges better for a not-insignificant advantage.

This second day felt way more in tune with the overall philosophy for the HB160. It’s a solid bike with a bit of personality, and chasing Guillaume down his local trails you can catch what it’s trying to say. Yeah, the numbers are a bit short and tall, and the head angle never felt quite as slack as advertised, but somehow that felt like details not to get hung up on, rather than the big picture. Maybe it’s just the romance of the story that gets under you skin, the uniqueness of the machine and the way it gets on with all the trails pointed at it that sucks you in by the end?

Hope might still programme that massive lathe to run for a week and cut the blanks for a longer, slacker 160mm frame in the future, and if it does, I’d love to try the result. Until any such bike’s produced though, it’s pure speculation whether it’d have half as much charisma as Hope’s managed to hammer into its own dream bike. Not just making another copycat product for a first bike is impressive, and the bloody-mindedness and the passion that’s gone into the HB160 is written all over it, and, ultimately, worthy of respect. Hope has played Top Trumps with itself and stuck its name on exactly what it wanted to, with as few compromises as it was willing to make. You have to tip your hat to that, and to a machine, the likes of which you’ll not see come around everyday.