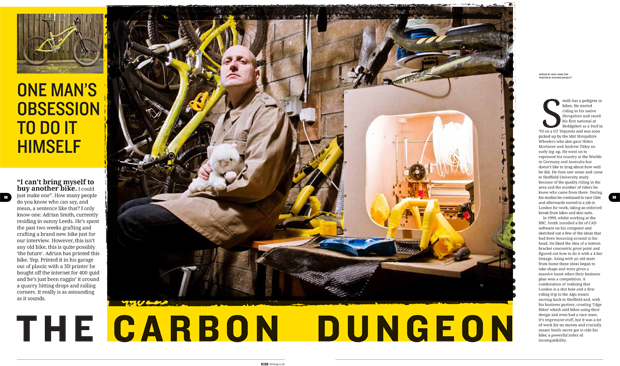

The latest issue of Dirt has an article I wrote about Adrian ‘Carbon Wasp’ Smith. The piece explains that Smith has been building his own bikes for years and that’s he’s been spending an unhealthy amount of time in his self inflicted carbon dungeon. Smith makes his own DIY full carbon full suss machines which ride much more beautifully than they look. In the latest iteration of ‘the carbon wasp’ he has embraced a new technique, he has Printed a bike. Literally. He’s used rapid prototyping technology, also known as 3D printing, and a printer he bought online for 400 quid. This enabled him to produce a new bike, specifically for the interview, in only 2 weeks (while working full time and going on holiday). The printed core is assembled then he wraps with carbon fibre to give it rigidity and strength, but as the article explains, it’s not as high tech as it sounds but works amazingly well.

You can find Adrian on twitter but he has his own website and a facebook group for DIY bike builders

Rapid prototyping has been maturing over the past 30 years to the point where you can now buy your own printer for hundreds rather than 10s of thousands of pounds. The technology is dripping down in to consumer products and even making its way in to the bike industry. It’s used extensively in the design and development process by bike, part and accessory manufactures to visualise the CAD data that is inevitably created.

However, like Smith, the process is finding it ways in to the manufacturing of components. The complete flexibility of process (other than material constraints) means that geometries or shapes previously unmanufacturable can become reality. Charge bikes have used a laser sintering process to produce titanium dropouts on their Ti Freezer frame.

Raceware industries have been manufacturing mounts for Garmins over the last year. Normally plastic components such as these would require very expensive tooling for each model in their range. However, with direct manufacture, they can just make to demand, the only limitation being the time it takes.

In other industries, Nike are now manufacturing the sole plate of their latest football boot using a laser sintering process of Nylon. The shape of the sole plate means that it could not be made with traditional manufacturing techniques. It has been completely optimised for performance without being limited by how it will be made.

Another implication for this type of manufacture is customisation. As each part is made individually of thousands of layers it can be changed to suit the user or purpose. The only limitation is the creation of the data that drive the machine, the CAD. A different but much more visually appealing application of this is this custom dress for Ditta Von Teese manufactured by Shapeways.

These machines and the software to run them have been finding their way in to schools and universities for years. Now that you can buy one to use at home for £400 quid the possibilities are endless. Their application and technologies will continue to find pervade our lives, the futures bright, the futures printed.

Update:

Here’s some of Adrian’s own production shots, it’ll give you an idea of the size of the constituent parts and how they jig-sawed together before being wrapped. Get adrian at [email protected]